BEIJING — The Rev. Peter Liu Yongbin, a wireless microphone tethered to

his head, gazed out over his prospective converts and plowed into the

ABCs of Roman Catholic faith. He offered a roughly abridged version of

Abraham’s family tree, the benefits of frequent confession and a quick

guide to church hierarchy. “Think of the pope as equivalent to the

minister of a government bureaucracy,” he explained.

Then came the pop quiz. What if

China

were to experience another Cultural Revolution, the traumatic decade of

Maoist zealotry during which religious adherents were persecuted?

“If a Red Guard puts a knife to your throat and tells you to renounce

your faith, what should you do?” he asked the five dozen initiates, all

of them weeks away from baptism. After an awkward silence, Father Liu

blurted out the answer: “Never give it up,” he said, his eyes widening

for effect. “Your devotion should be to God above all else.”

Such sentiments might be a mainstay of Christian belief but they border on treasonous in China, an officially

atheist

state that demands fealty to the Communist Party. The pope might be a

ranking minister, but according to the party’s thinking, President Hu

Jintao is Catholicism’s supreme leader, at least here in China.

As a priest at an officially sanctioned government church — as opposed

to the legion of illicit unofficial congregations — Father Liu struggles

to balance his faith with the often-intrusive dictates of the Chinese

Catholic Patriotic Association, the omnipotent government body that

oversees religious life for China’s 12 million Roman Catholics. (Nearly

half of China’s Catholics are thought to attend underground churches.)

It is a balancing act shared by the leadership of China’s four other

official religions — Protestantism, Islam, Buddhism and Taoism — who

must answer both to state authority and the exigencies of their faith.

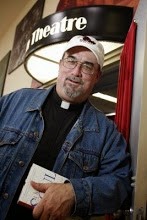

An irascible but deeply contemplative man whose knowledge of Marxist

dogma rivals his command of biblical verse, Father Liu, 46, is quick to

praise the past three decades of increasing openness that has paved the

way for religious revival across the land. But even as he declares

himself steadfastly apolitical, he acknowledges that these are trying

times for state-supervised clergy members.

“Sometimes the political pressures are exhausting,” he said as he sat in

his church office only a few blocks from the closed compound housing

China’s leadership. The walls of his office are dominated by a Chinese

flag and a crucifix.

Such pressures have been rising as Beijing and the

Vatican

engage in an increasingly combative struggle over the appointment of

bishops. After several years of quiet negotiation and a tacit agreement

to jointly name Chinese bishops, the Patriotic Association has since

2010 consecrated four bishops over the Vatican’s objections, including

Joseph Yue Fusheng, who was ordained Friday in the northern city of

Harbin.

Rome responded with an automatic excommunication.

The drama intensified on Saturday, when the Rev. Thaddeus Ma Daqin, the

newly installed auxiliary bishop of Shanghai, stunned his congregation

by announcing his resignation from the Chinese Patriotic Catholic

Association. “In the light of the teaching of our mother church, as I

now serve as a bishop, I should focus on pastoral work and

evangelization,” Bishop Ma told the crowded church. “Therefore, from

this day of consecration, it will no longer be convenient for me to be a

member of the patriotic association.”

The announcement,

captured on video

and posted on foreign and Chinese Web sites, was met with sustained

applause from the congregation. Father Ma, who did not lead Mass on

Sunday as scheduled, has not been heard from since. China has responded

to the impasse with bravado, calling the recent excommunications

“unreasonable and rude” and suggesting that it will continue to

unilaterally fill as many as 40 vacant bishop seats. The Patriotic

Association declined to comment for this article, as did the Vatican.

Catholic leaders who have spent years fostering détente between Rome and

Beijing worry about the possibility of a catastrophic schism, something

avoided during the darkest days of the Communist Party’s war on

religion.

“It’s a very critical situation; I haven’t seen things so bad in 50

years,” said the Rev. Jeroom Heyndrickx, founder of an institute at the

Catholic University of Leuven in Belgium that promotes dialogue between

China and the church. “All the years of cooperation and progress have

been torn to pieces.”

It is not entirely clear what went wrong. The animus, fed by an age-old

narrative that paints the Vatican as a foreign interloper, is never far

beneath the surface. But analysts suggest party hard-liners may be

taking advantage of the political stasis that has preceded the

once-a-decade leadership change scheduled for later this year.

Many religious leaders both in China and abroad say the effort to turn

Catholics away from the pope have largely failed. The Rev. Bernardo

Cervellera, editor in chief of AsiaNews, an official Vatican news

service, said the government’s recent ordinations had angered many

ordinary Catholics. “I would say there’s a kind of resistance against

these bishops, with the faithful refusing to attend religious ceremonies

when they are present,” he said.

The conflict is reflected in Father Liu’s church, the Cathedral of the

Immaculate Conception, which dates back to 1605, when Wanli, the Ming

dynasty Emperor, permitted the Italian Jesuit Matteo Ricci to build a

residence and small chapel near the site of the current church. More

commonly known by its Chinese name, Nantang, or South Cathedral, it has a

storied but turbulent past. Repeatedly destroyed by earthquakes and

fires, it was burned down during the Boxer Rebellion of 1900 and closed

for much of the Cultural Revolution. In 1971, the soaring, gray-brick

Baroque cathedral was quietly reopened for foreign diplomats, and less

than a decade later, to Chinese.

Home to Beijing’s bishop, the church ministers to a fast-growing

congregation, much of it increasingly young, college-educated and hungry

for a moral antidote to China’s rampant materialism and corruption.

Like many members, Liu Bin, 25, said he felt wounded by the government’s

increasing antagonism toward Rome. “The Vatican to me is like Mecca is

to the Muslims,” said Mr. Liu, a software designer. “The pope is

essential to our faith.”

Father Liu’s days are long, with the first Mass starting at 6 a.m. and

the last one, a lively musical youth service on weekends, ending at 8:30

p.m. Some days he officiates at eight weddings, most of them for

agnostic couples entranced by the pomp and the European-style

architecture. During Christmas, traffic in front of the church snarls as

20,000 people pour through the nave. Father Liu estimates that

three-fourths of those who come are drawn by the music and the costumed

Santas.

“Most Chinese people have no idea what Christianity is,” Father Liu

said, looking rumpled after a particularly hectic weekend. “They’ll come

here to get married, and then go off to a Buddhist temple.”

Not that he minds. In fact, the $450 he receives for each wedding helped

pay for radiators last year, alleviating bitterly cold services where

supplicants’ fingers would sometimes stick to frozen chalices.

Drawing the curious is good for other reasons: it is one of the few ways

the church can legally proselytize. Rigorous state control means that

China has no Christian radio shows; Bibles cannot be sold at bookstores

or passed out on the street. Religious organizations are barred from

accepting foreign donations for charitable work.

“We have to beg the government to do anything,” he said, yanking at his

collar for effect. “Their attitude is, ‘You should be happy we allow you

to exist.’ It’s not like in the West where all your political leaders

are already Christian.”

Like many Catholic clerics, Father Liu comes from a family of the

faithful. Before the Cultural Revolution forced a name change, his

hometown in Shanxi Province was called New Catholic Village. Since 1949,

it has produced 25 priests, 30 nuns and a bishop. “I learned to say the

word ‘Lord’ before I could say ‘Mama,’ ” he said.

A cocky, longhaired troublemaker in his youth, he says he was largely

oblivious to religion until, one day after graduating from high school,

he suddenly felt the calling. He shaved his head, started wearing suits

and immersed himself in the Bible. After four years studying philosophy

in Beijing, he entered the seminary with the help of a bishop impressed

by his charisma and intellect. “The church prefers extroverts like me

because others tend to follow us,” he said.

But government strictures on religion and the continuing battle between

Rome and the Communist Party have tested his faith. Sometimes, he said,

he dreams of living abroad.

Then there are other challenges, including a growing shortage of priests

and nuns. In the past, he said, religious families like his would be

happy for a son to enter the priesthood. There was the prestige, but

also the benefits of a steady meal. These days, the country’s strict

family planning laws dissuade most families from giving up their only

child to the church.

Experts say that clerical celibacy and the strife between the Vatican

and Beijing have made it harder for Catholicism to compete with the

rapidly growing Protestant faith, which has five times as many

adherents. “In the Protestant Church, anyone can be a pastor and you

don’t have a problem with the pope, who is considered a so-called

foreign power,” said Father Cervellera of AsiaNews.

Still, about 500 people last year were baptized at Nantang, up from 200

in 2006. The conversion classes can be exhausting because most newcomers

know little about Christianity. At a recent session, those gathered

asked whether Catholicism would prolong their lives or make them rich.

“Will Catholicism make me get along better with other people?” asked an

elderly man who described himself as a misanthrope. (“The church will

give you dignity,” Father Liu responded. “Religion will make you

perfect.”)

Despite the challenges, Father Liu is optimistic about Catholicism’s

future in China. Religion will outlast any political party, he says, and

then there is the sheer number of the unaffiliated. “As far as I’m

concerned,” he said, “there are at least 1.2 billion people here waiting

to be converted.”

Ian Johnson contributed reporting, and Shi Da contributed research.